Research shows that a high price is cited as the main barrier to not purchasing sustainable products. How do you deal with this as a provider of sustainable products? This article looks at the prices of sustainable products from different perspectives. Using psychological theories and practical examples, options are discussed to make products appear less expensive.

Sustainably produced products are in many cases more expensive than products that are not sustainably produced. This means that it can be challenging to sell these products. After all, consumers shop price-consciously. In most cases, a higher price for a product is considered less attractive than a lower price.

Research into sustainable prices

Research is conducted into the price of sustainable products in various ways. This creates a better picture of how consumers view the prices of sustainable products, and how this can best be dealt with as a supplier.

Survey

The image above shows the results of a 2021 survey that asked 4,000 people aged 16-64 from the UK and US what they saw as the main barriers to purchasing eco-friendly products. It was possible for the participants to tick multiple barriers.

Barriers to buying eco-friendly products:

- High price of products (60%)

- Difficult to find eco-friendly products/brands (24%)

- Not enough information about what eco-friendly means (19%)

- Not familiar with eco-friendly brands / prefer to stick with brands they know (19%)

- Lack of clarity about the benefits/value of eco-friendly products (14%)

- Doesn't think eco-friendly products are as effective as regular ones (11%)

- Does not think individual impact makes a difference (10%)

What appears to be that more than half of the people interviewed (also) gave the high price of sustainable products as a reason for not buying them or buying them less. Although the other points certainly offer interesting starting points, because of that high percentage, this article will focus on the high price of sustainable products.

Added value

Compared to non-sustainable products, sustainable products are often relatively expensive. For example, at Asket you pay around €130 for a sustainable shirt, while at Primark you only pay €10 for a non-sustainable version. Now that comparison is of course not entirely fair. In addition to a difference in durability, you also pay for a difference in quality. If you compare the price of this Asket shirt, for example, with non-sustainable shirts from Hugo Boss (€ 120) or Ralph Lauren (€ 140), then the € 130 of the sustainable Asket shirt suddenly seems a lot less expensive. And then we don't even compare against 'designer' shirts from brands like Tom Ford (€ 650), Versace (€ 700), or Gucci (€ 780). Compared to that, the Asket shirt seems like a bargain.

Now I understand that not everyone is willing to pay €130 for a shirt (myself included). But for the group of people who now buy unsustainable shirts from brands such as Hugo Boss or Ralph Lauren, a sustainable shirt like that from Asket could be an excellent alternative. For them, the high costs would not be a problem in an absolute sense, but rather that they consider the costs too high compared to what they get for the money. For example, by making it clearer to sustainable companies what their added value is, this could possibly ensure that a larger group of people are willing to pay the 'high price' for sustainable products.

This example uses shirts, but a similar comparison applies just as well to products such as toys, jewelry, care products, food, etc.

Premiums

In 2007, research was published into the price perception of organic products. This showed that consumers were willing to pay about 10-20% more for organic products compared to non-organic products. The demand for organic products subsequently declined sharply at so-called premiums above 20%. Since many organic products are up to 50-100% more expensive than non-organic products, the researchers say it is perhaps not surprising that relatively few organic products are still sold. This is even despite the fact that people are increasingly indicating that they want to buy such organic products and that stores these days have an increasingly large organic range.

True pricing

The organization True Price states that social and environmental costs that arise as a result of the production of a product should also be included in the price. In this way the 'true price' of a product is created. Viewed through that lens, sustainable products are not so much very expensive, but many cheap products are also very cheap. The same €10 shirt from Primark would probably have a significantly higher price tag when the impact on society and the environment is taken into account. The Asket shirt, on the other hand, would remain roughly the same price as it is now. This makes sustainable products a lot cheaper in comparison.

Future

In an article called The cost of buying green, Deloitte describes that sustainable products are still at the beginning of their product life cycle. Just as flat TVs were not affordable for the average citizen a few years ago, the same may now also apply to sustainable products. As the market for sustainable products matures, it is expected that prices will also fall. This makes sustainable products affordable for a larger target group. An example of this described in an article by Project Cece is that sustainable clothing is often more expensive at the moment because they simply do not yet have the economies of scale that non-sustainable clothing does.

Sustainable prices and psychology

From psychology there are a lot of concepts, heuristics, and theories that can be applied to the prices of sustainable products. They often relate to how prices are perceived by people or how they are viewed in a particular context.

Pain of paying

The pain of paying is the emotional stress or discomfort associated with paying for something. It is usually experienced with a one-time, large payment or with a purchase that seems too expensive or unaffordable. How much money needs to be spent in absolute terms also plays a role.

This concept is very relevant in the context of sustainable products as many people may feel that sustainable products are too expensive or out of their budget. However, there are strategies that companies can try to ease the pain associated with "overpaying" for certain sustainable products or services.

- Offer flexible payment options (such as paying afterwards or in installments)

- Discounts or promotions (e.g. "1 + 1 free")

- Give extras as a gift (such as loyalty points)

- Eliminate costs (such as free shipping above a certain order value)

Price perception

The concept of 'price perception' is explained in several ways by others. However, in this article it is meant that the price serves as an indicator for consumers to determine whether or not they belong to the target group of a particular product.

For example, the high price of a sustainable product can cause people to think that these products are not intended for them. For example, research conducted in 2011 showed that more than 50% of them felt that green products target "rich elitist snobs" and "crunchy granola hippies".

Conversely, a perceived 'too low' price sometimes has undesirable effects. This could send a signal that the people who buy these products could not afford more expensive products. It may also lead to consumers thinking that these products are of lower quality than more expensive alternatives. In addition, the so-called costly signaling theory also plays a role here. It states that people (just like animals) send signals to their environment based on the choices they make and the behaviors they exhibit. In that context, purchasing expensive sustainable products sends a signal to the environment that they are environmentally conscious people. A status they are probably proud of. However, if sustainable products were no longer expensive, the 'cost' of purchasing them would be lower, which may also partly eliminate their status as environmentally conscious people.

Loss aversion

The term loss aversion refers to people's tendency to avoid losses (or pain associated with losses), even when there are greater potential rewards from taking a risk. The bottom line is that we have a greater emotional response to losing something than to gaining something of equal value (or in some cases even greater value than the alternative).

This principle can be excellently applied as part of a sustainable webshop optimization process. For example, sustainable companies can try the following tactics:

- This way you can work with try

before you buy. In this way you reduce the perceived risk that

consumers run with their purchase and therefore increase the chance

that they will convert.

This principle can also be combined with scarcity. For example, you can work with temporary offers. This will ensure that consumers 'lose' access to this cheaper sustainable product after the offer period has expired (and will therefore be more inclined to make a purchase).

Furthermore, a moneyback guarantee could be considered. This can also significantly reduce the risk of a 'loss' and thus increase the chance of a purchase.

Finally, you can also use the principle in reverse. For example, consider pointing out the negative consequences that consumers would experience if they did not purchase certain sustainable products.

Social proof

The idea of social proof is that we are influenced by the people around us (both unconsciously and consciously). In other words, we often make decisions based on what we see other people doing.

Because social proof is such a broad principle, you can use it in various ways.

- This way you can show positive feedback from consumers who have

already purchased the products in the form of product reviews.

You can also create content that shows visitors to your webshop how other people use the products or services (and why it makes them so happy).

In addition, testimonials (also known as 'references') are of course a well-known form of social proof online.

You can also consider using famous people, influencers, or experts to promote the products.

Availability heuristic

The availability heuristic refers to our tendency to use information that is readily available in our memory (such as examples or facts we have recently encountered). For example, we are more likely to choose something if we can easily visualize or remember it (over other options that are equally good or affordable). As a result, we often choose from the first few choices that come to mind.

This heuristic can be used in several ways to increase sales of sustainable products:

- This way, ecommerce retailers can more often place sustainable products on the homepage of their webshop. This way, these products are more 'top of mind' and may therefore be sold more often.

- They can also ensure that sustainable products are more visible and accessible. An example of this is to display the more sustainable options higher on category pages by optimizing the sort order accordingly.

- For example, sustainable up-sells or cross-sells can also be shown more often.

Free and non-binding 1 hour session?

Gain insight into your challenges surrounding CRO

Anchoring

The psychological principle of anchoring refers to our tendency to use the first piece of information we hear as a reference point to make decisions (even when that information is of little or no relevance).

Ecommerce companies can use this cognitive bias by, for example:

- First show relatively expensive products with high margins. Products that follow then seem a lot more affordable in comparison.

- Compare the price to something of a similar value. Instead of consumers comparing the Asket shirt against a shirt from Primark, you could, for example, indicate that shirts of comparable quality have approximately the same price.

- As a company, produce more content about sustainable items. This increases the likelihood that consumers will begin their shopping process by exploring these popular products, rather than looking at lesser-known (cheaper) options.

- Offer multiple price levels for their products and services. This allows consumers to compare prices and decide which offer offers the best value for money based on their own budget and needs.

Cognitive dissonance

The psychological concept of cognitive dissonance refers to a feeling of discomfort or stress that we experience when we encounter conflicting thoughts or actions. This can arise, for example, when our thoughts (I care about the planet) are not in line with our actions (I do not buy sustainable products).

Because cognitive dissonance can arise between different conflicting thoughts and actions, the ways to resolve this are also broad.

- For example, online retailers can create content that explains to visitors the negative consequences of purchasing unsustainable products. Or conversely, what positive consequences buying sustainable products has.

- Ensure that consumers do not have to choose between 'sustainable' and 'quality', but ensure that the products have both these characteristics.

Diderot effect

The Diderot effect refers to our tendency to align consumption patterns with our 'social identity'. For example, if we buy a new jacket of a certain quality, we may also want a new wallet or necklace of the same perceived quality as the jacket.

In the context of sustainable living and consumer psychology, the Diderot effect can be used in a powerful way. What you can do is combine the Diderot effect with the Foot in the door technique. The aim is to get consumers to buy one or more sustainable items (for example by offering them an 'introductory' discount). The possible consequence of this is that their 'identity' slowly shifts towards sustainability. As a result of the Diderot effect, these consumers will then start wanting more sustainable items because they will then match their new identity as a sustainable person.

Priming

The psychological concept of priming refers to the tendency of people to respond more quickly to words or actions associated with a particular stimulus (such as an emotional state or memory).

Applied to selling sustainable products online, retailers can, for example:

- Put images on their product pages where people wear the products or use the products in a sustainable context. This can make it easier for them to see themselves using these products.

- Alternatively, it may be an idea to AB test whether creating positive associations with their product leads to better results. You can think of showing certain images or words that are related to sustainability and nature (such as 'green' and 'healthy').

Reframing

The cognitive psychological concept of reframing refers to seeing things in a different light.

- An example of this is not to sell sustainable products as 'sustainable', but to focus on the high quality or additional benefits of that product. For example, on the product page of the Tesla Model 3 there is little or no discussion about how sustainable the car is, but instead focuses almost exclusively on the high quality of the car.

- They can compare the price of the product in a different way. For example, Asket shows what their products would cost if you bought them from a retailer instead of directly through their webshop.

- An alternative is to show the costs as a cost per use. This way, visitors see that each time an item is used it only costs a small amount instead of the relatively high purchase amount.

Examples pricing sustainable products

Sustainable web shops use various methods to make the prices of their products appear less expensive. Curious how this would work on your own webshop? Using conversion optimization techniques such as A/B testing or user testing, these changes can be investigated leading to an increased conversion rate and, as a result, more sales.

Bundling

By offering products as part of bundles, you make it more difficult for consumers to directly compare prices with other products. In addition, (because with a bundle you sell multiple items at the same time) you can often also give a discount compared to selling the items in the bundle separately. This way, psychologically speaking, you kill two birds with one stone.

For example, Honest offers bundles of sustainable care products.

Installments

Some parties choose to allow payment in installments. Especially if you offer this without interest, it can be interesting for visitors to choose this. After all, they do not have to pay a large amount immediately, but can do this in smaller blocks.

An example of this is the company Honeysticks. What is also striking about this website is that they choose to keep the shopping cart visible in the checkout. This means visitors need fewer page views, which is a sustainable best practice.

Segmenting

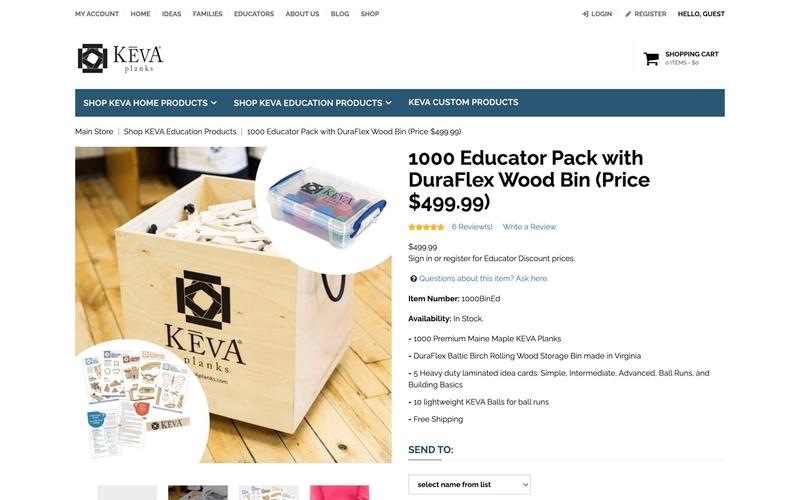

It is also possible to charge different prices for certain groups of consumers. For example, you can consider a discount for foundations, schools, or people from certain countries. Offering these lower prices can ensure that those parties choose sustainable options, while they may not have done so at the regular prices.

For example, Keva offers planks discounts for schools. Especially since they may purchase in large volumes, this can be a win-win for both parties.

Buy now, pay later

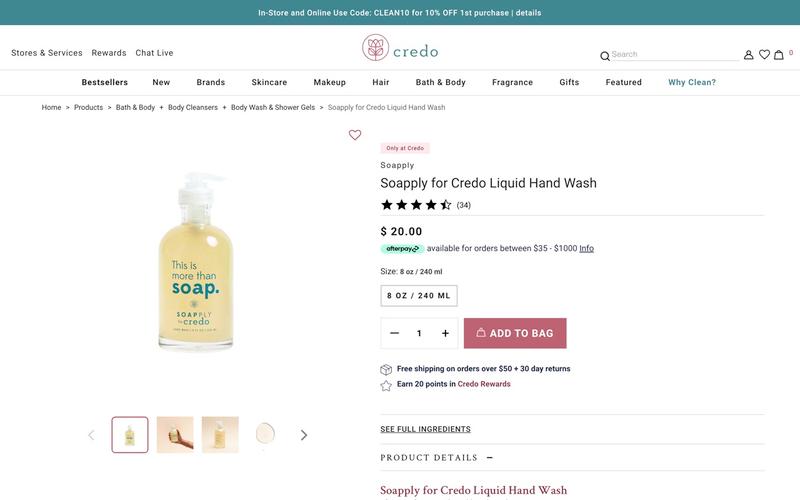

Various web shops also choose to offer 'buy now, pay later' options in their checkout. Here too, this option is more attractive if there is no interest to be paid with this option.

For example, the beauty retailer Credo offers this option (for certain order values) via Afterpay.

Newsletter

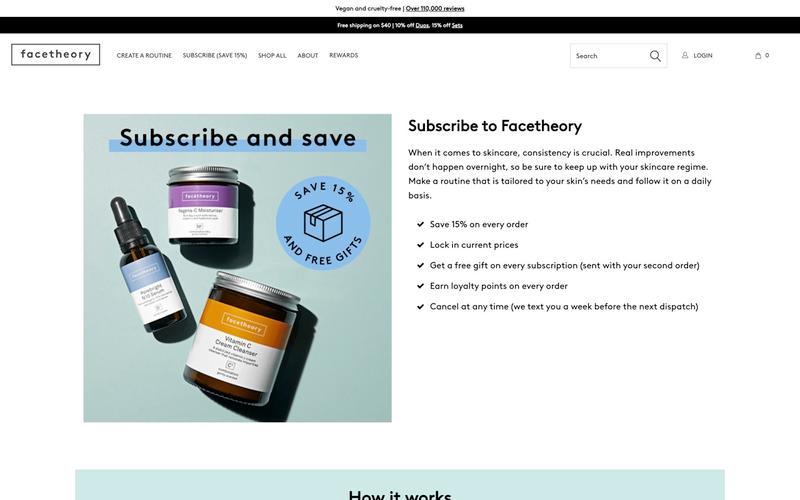

Many sustainable web shops also offer the opportunity to get a discount when you register for their newsletter. The advantage they get from this is that they get permission to keep you regularly informed about their products and services.

For example, care product provider Facetheory offers a 15% discount on the first order when subscribing to their newsletter. Also promising are a free gift and loyalty points. An interesting point about this company is that they are transparent about the ingredients in their products.

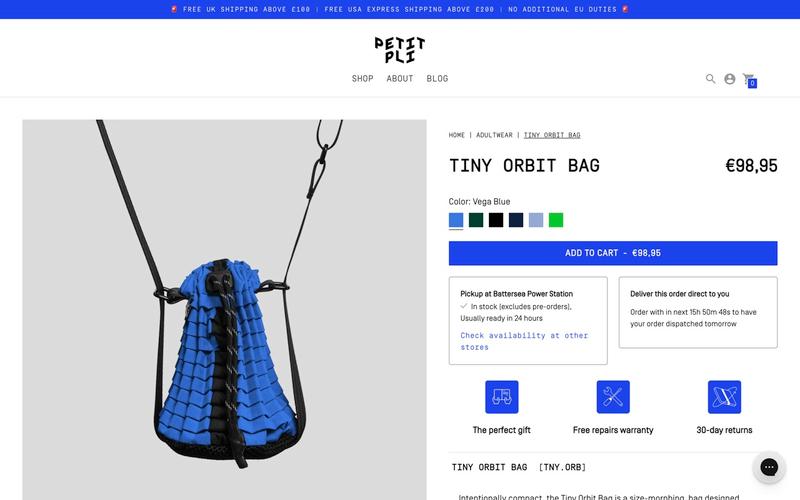

Free repair warranty

Various clothing brands now also offer free repairs of the clothing they sell. Not only does this make it easier for consumers to be persuaded to make a purchase, it also ensures that clothing lasts much longer, which is of course good for the climate.

Examples of these types of companies are Petit Pli and Patagonia.

Trade-in discount

In addition, there are parties that offer a discount when you hand in old products to them. Often these products are then refurbished and resold as second-hand items or passed on to people in poorer areas.

A good example of this is sustainable toy supplier Plan Toys, which collects toys via Toy Cycle.

Cost per use

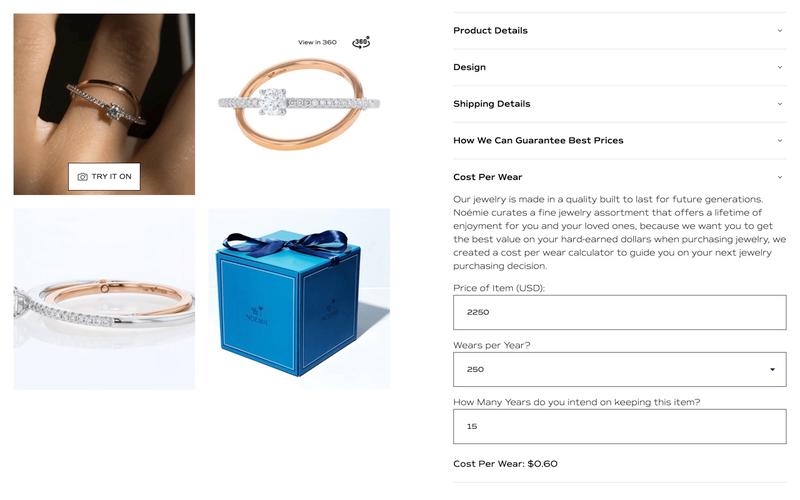

An example of the concept of 'reframing' explained earlier is to show the cost per use. This can have good effects, especially when you sell relatively expensive products that are often used.

Hello Noemie jewelry has a hefty price tag. However, if you calculate this back to a cost per use, you sometimes end up with less than a euro per use.

Volume discount

Another alternative is to lower the price as a greater volume of products is purchased by the consumer. This also effectively creates a win-win because the consumer receives a lower price per piece while the retailer receives a higher order value.

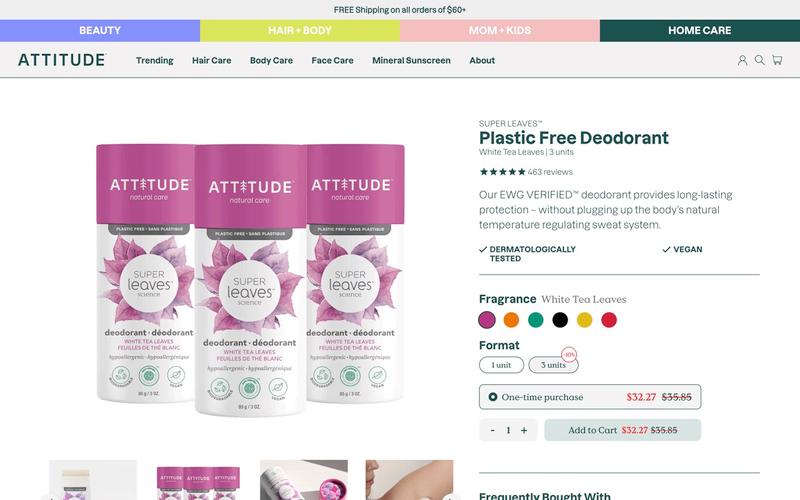

For example, manufacturer of sustainable care products Attitude gives a 10% discount on an order of two products compared to when only one product is ordered.

Incremental discount

It is also possible to let the discount grow with the quantity of products ordered. Even more so than with a regular volume discount, this can cause consumers to order larger quantities of products at once. An additional advantage is that less CO₂ will be released when transporting one large order instead of individual packages each time.

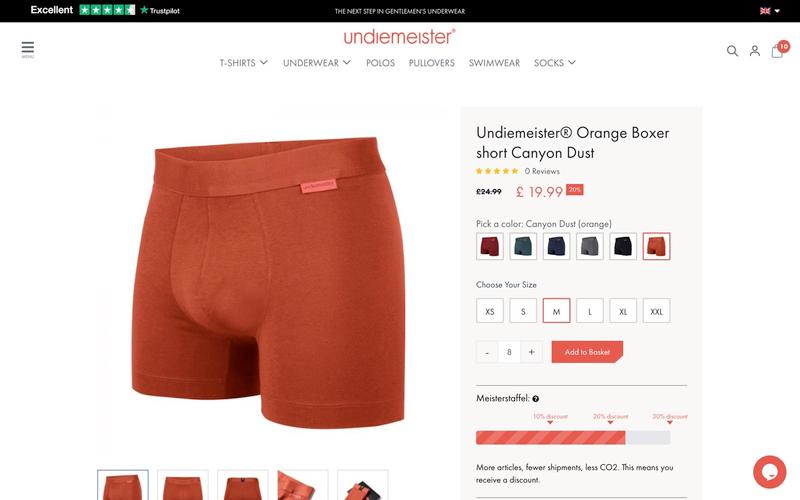

Underwear manufacturer Undiemeister, for example, uses such a 'volume discount' whereby increasingly larger discounts are applied as the number of products ordered increases.

Subscription

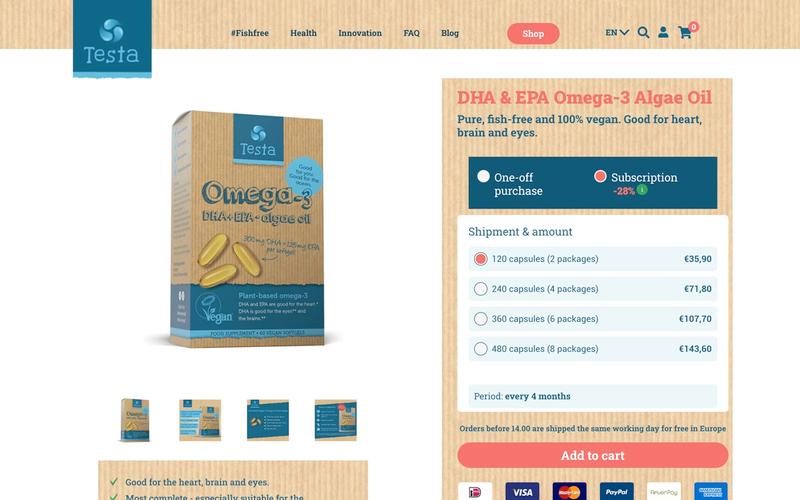

In addition, there are more and more parties that offer discounts when a subscription is taken out for their products. The most logical sector for this is food and drinks, but various providers of care products are also starting to offer this.

For example, producer of sustainable omega 3 oil Testa gives a discount of up to 28% when their products are ordered in subscription form compared to individual sales. An additional advantage for consumers is that they do not have to place a new order every time, but simply receive the new products in their mailbox when the old ones run out.

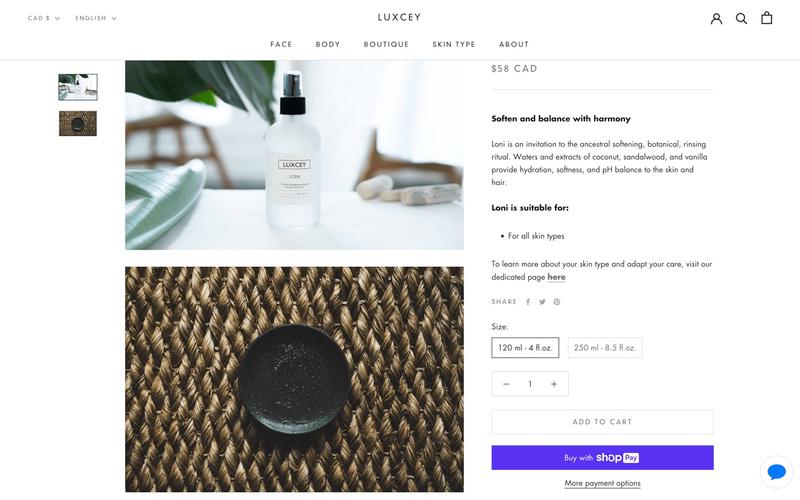

Container size

Instead of giving a discount when purchasing multiple products, you can also reduce costs when purchasing larger packages. This is effectively a form of 'cost per use', but in a different form.

For example, if you buy care products in larger packaging from Luxcey, you effectively pay fewer euros per milliliter. In this case, this has the additional advantage that less plastic needs to be used as packaging material. It is also interesting to see that this party uses sustainable hosting for their website.

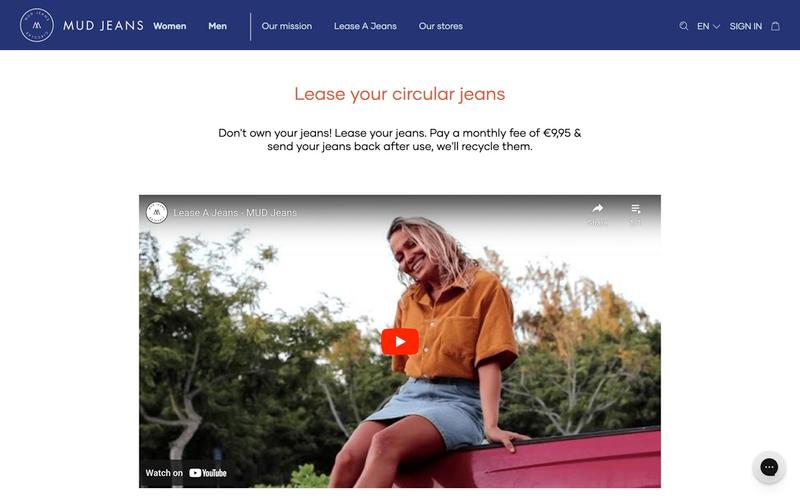

Monthly lease

It is also possible to 'lease' sustainable products instead of selling them directly. This will significantly reduce the initial cost of purchase, meaning more people will be able to make a purchase. This method of pricing may be more in line with other subscription types such as Netflix and Spotify, for which we are also used to paying per month and not the entire amount in advance at once.

A well-known example of this is the Dutch Mud Jeans, which charges a monthly amount for their trousers. After payment of the monthly amounts, the jeans are yours. What is striking about the Mud Jeans product pages is that they use clear photos and ask good questions about the fitting sizes. This may mean that they receive fewer returns.

Conclusion

Sustainable products currently often have a (considerably) higher price tag than the non-sustainable variants. This can lead to consumers often ignoring these items. Based on the research described, the psychological theories, and the practical examples, companies may be able to ensure that these prices appear less high, which will benefit conversion.